By JOHN T. WARD

One is that they’re a favored meal or sea nettles, larger jellyfish also known for their sting. Another is that, for this summer at least, the sea nettles may have eaten them all.

“They’re kind of gone for the season,” Paul Bologna, director of marine biology and coastal sciences at Montclair State University, told attendees at a Rally for the Navesink organized by Clean Ocean Action and other environmental groups and held at the First Presbyterian Church.

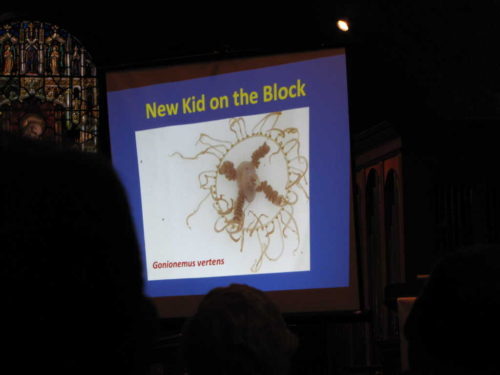

The clinging jellyfish, a Pacific native that appeared on the East Coast in Massachusetts in the 1990s, was first reported at the New Jersey shore in May. In June, a Lincroft man was hospitalized after he was stung while wading in the Shrewsbury River.

Clinging jellyfish “are really dangerous in terms of human health considerations,” Bologna said. “They’ve got a really toxic punch. They’re going to send you to the hospital.”

With funding from the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Bologna said his lab looked into the local distribution of the clingers, which generated “numerous” sighting reports in the Shrewsbury River. But there were few in Barnegat Bay, where conditions were expected to be ideal. Why?

“Sea nettles eat clinging jellyfish,” he said. “The reason we may not see many clinging jellyfish in Barnegat Bay is that we’ve got a huge bloom of sea nettles there.”

The rare, or at least previously unreported presence, of clinging jellyfish, along with elevated bacterial levels in the Navesink, prompted the Navesink Maritime Heritage Association to cancel this summer’s River Ranger program.

NMHA trustee Rik Van Hemmen asked Bologna if evidence suggested that the organization should delay next year’s River Rangers program until later in the summer. That’s a question that can’t yet be answered, Bologna said.

“I don’t know if they’re going to bloom tomorrow or next year or in 10 years,” he said of the animal’s polyps, which cling to eelgrass in and around docks.

The Sandy Hook-based American Littoral Society, which is working with Bologna’s lab, is hoping to get a closer look at the polyps, and is asking the public to report sightings. Reports may be made by email ([email protected]) or via the Marine Defenders App, downloadable for iPhone but not yet available for Android devices.

The organization also hopes to hear from riverfront property owners who will allow their docks or bulkheads to be sampled for clinging jellyfish.